Predatory Practices in the Retail Electricity Market

Samantha Fox and Alberto Lamadrid are collaborating across their Lehigh colleges to increase scholarship on the retail electricity market and develop accessible information for consumers to confront and combat the market’s predatory practices.

Historically, one company generated and supplied electricity to all residents in a designated region. These monopolies are referred to as default providers, including PPL in the Lehigh Valley and PECO in the Philadelphia area. The Public Utility Commission regulates the default companies and must approve any change the companies make to their electricity rates, ensuring the new rates are necessary and non-exploitative.

In the past three decades, there have been changes to the marketplace. Fox mentions that “legislation that was passed in the early 90s on the federal level allowed for states to basically authorize new entrance into the electricity market to compete with what's called the default provider.” Although the default provider continues to remain the largest provider in a given area, the Energy Policy Act of 1992 allowed for new entrance into the market. “The idea behind this was that it would allow for companies that were generating electricity through renewable means [to] more easily enter the marketplace and sell that electricity to other companies that might deliver to consumers,” says Fox.

Allowing for competition in the marketplace was sought to increase consumer choice, giving residents the opportunity to decide between the default provider and retail suppliers offering electricity from renewable means. Although this is supposed to work in the favor of consumers, “it has not played out in a way that is necessarily in the best interest of consumers all the time because these new entrances are deregulated. They do not have to justify their prices to anyone and can charge what they think the market can bear,” says Fox. The Public Utility Commission does not oversee retail suppliers and approve rate changes as they do for the default providers.

This lack of regulation has posed challenges for consumers and led to predatory practices. Retail suppliers have signed consumers up without their consent, withheld information, and increased confusion. Fox notes that “in Ohio, there have been companies that sign people up without their knowledge and consent, and say I’m coming to check your electric meter, and they’re actually signing you up for an offer.”

Suppliers will also try to give consumers fixed rates that sound appealing, but in areas with older housing that do not use electricity for heat, air-conditioning, or cooking (a household that uses low-levels of electricity), paying a fixed rate is significantly higher than a consumer would pay if their plan was variable, and they were only charged for what they consumed. Companies are intentionally unclear about what is the most beneficial for a consumer.

Lamadrid also explains that every resident in a service area receives a bill that looks practically identical. Even if a consumer is using a retail provider, their bill will come from the default provider so “people did not even know that they had been changed to another provider,” says Lamadrid. There is only one small line that indicates a consumers’ actual provider.

These are a few examples of harmful practices suppliers use to take advantage of consumers. In addition, suppliers target certain residents and neighborhoods. They are “praying on low information consumers, the elderly, people that are not active shoppers,” says Fox. Suppliers target consumers who are not actively shopping for lower rates on the Public Utility website, overtly lying to consumers “saying we’re gonna give you the lowest offer available but it's not by any means the lowest offer available,” says Fox. The suppliers purposefully seek out people who consume less information about the process, understanding less about ideal rates.

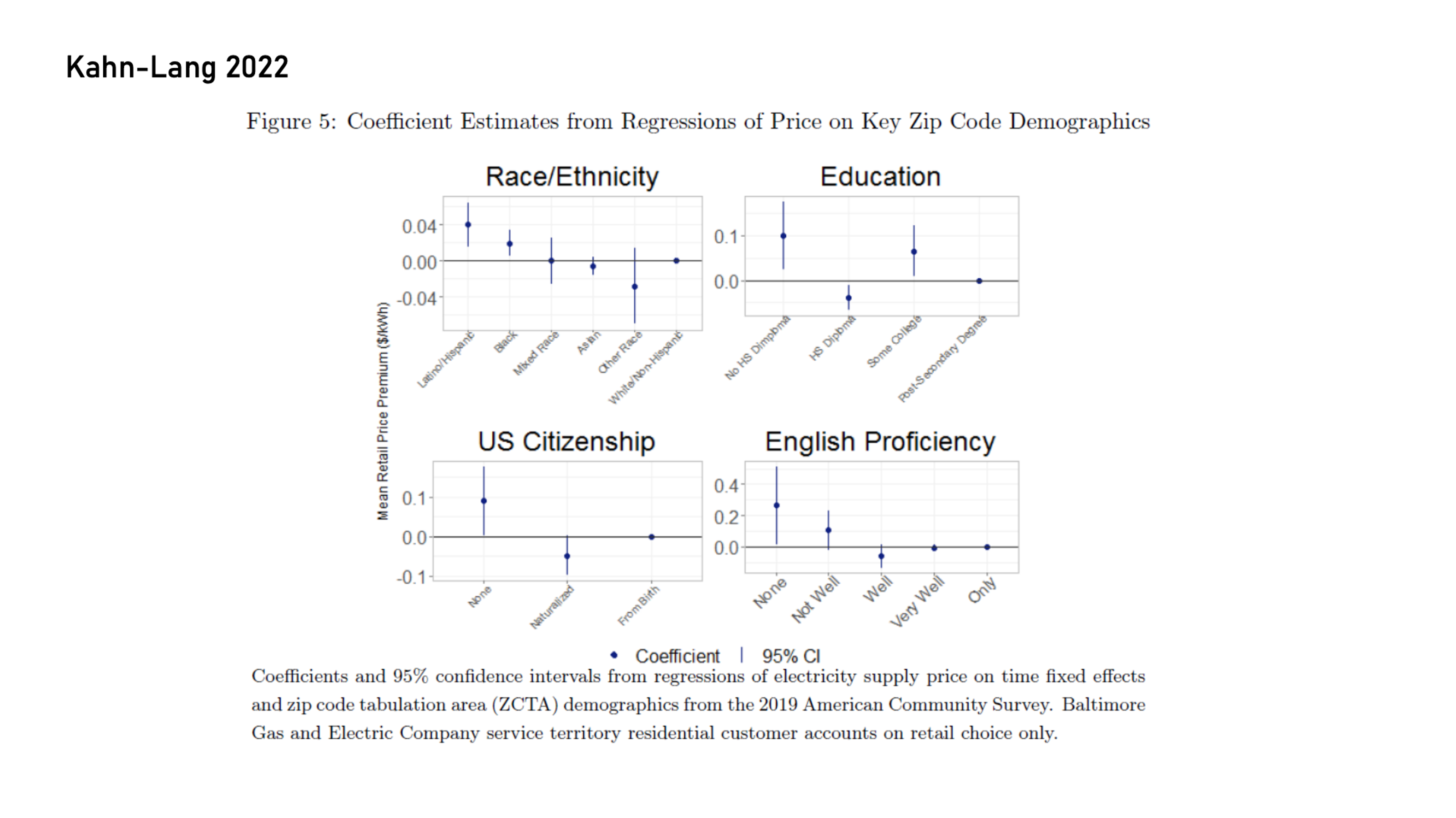

Fox and Lamadrid reference a Baltimore study to explain how suppliers are also targeting demographics of people. The study identified that “according to your citizenship, certain groups [are] more targeted than others and same thing with English proficiency…In some cases, areas in which there [are] lower levels of English proficiency, they seem to get more targeted by some of these companies,” says Lamadrid. Researchers, in the same study, also identified that “as your income goes up, the number of suppliers [trying to encourage a resident to switch companies] starts going down,” says Lamadrid. Suppliers are targeting vulnerable communities, who have lower levels of English proficiency to digest new contracts and bills, and are lower-income, misleading residents who have less room to spend more on electricity.

The lack of regulation has led to predatory and targeted practices. Fox and Lamadrid note that more accessible information can help combat these issues. “There is much less scholarship on retail electricity suppliers… these companies are understudied,” says Fox. They hope to close this concerning knowledge gap, interviewing residents on their experiences with retail suppliers and informing residents about what is happening. Lamadrid notes that “to some people it is a surprise that you can choose a provider”–evident that increasing education on the process would be beneficial.

In addition, Fox and Lamadrid want to understand the choices consumers are making: are residents intentionally switching providers, have suppliers come to residents' doors, do residents know the pros and cons of the provider they are currently using? If you would like to participate and share your experiences, it would be greatly valuable.

Since Fox and Lamadrid are also partnering with professors from Ohio State University, and have received significant funding from the Sloan Foundation, the scope and reach of their work has grown to residents in Pennsylvania and Ohio.